Posted on October 15, 2015

They tell on themselves: Stories of runaways and soldiers at Mission San Miguel

Just before sunset, we gathered outside the San Miguel mission cemetery, holding hands as Patti Dunton of the Salinan Tribe led a prayer and walked around us, singing a Salinan blessing song with a bull kelp rattle. She welcomed us and shared kind words of support and gratitude.

“We’re here today to honor our ancestors and those who came before us,” Patti Dunton said. “Thank you for getting the message out, thank you for getting the truth out. May you have strength to finish your journey. May you touch people’s hearts, so that they can understand the hurt from the past, that they might open their hearts up so we can heal the future, for all.”

While we were holding our circle outside the cemetery, the mission grounds were bustling with activity, as a Catholic wedding was underway. The gate to the cemetery was chained shut, so we asked the staff at the visitor center if they could let us in. They declined to grant us entry, stating that it was closed for repairs. We carried on with our circle, taking turns sharing reflections and stories pertaining to the mission.

Mission San Miguel is still owned by the Catholic church, and most of the facility is off limits to the public because it is still in use as a friary. Inside the halls and rooms they maintain for tourists, a predictably rosy depiction of the mission’s heyday is illustrated by various signs and interpretive panels. And yet, looking around, the darkness of the past was hidden in plain sight.

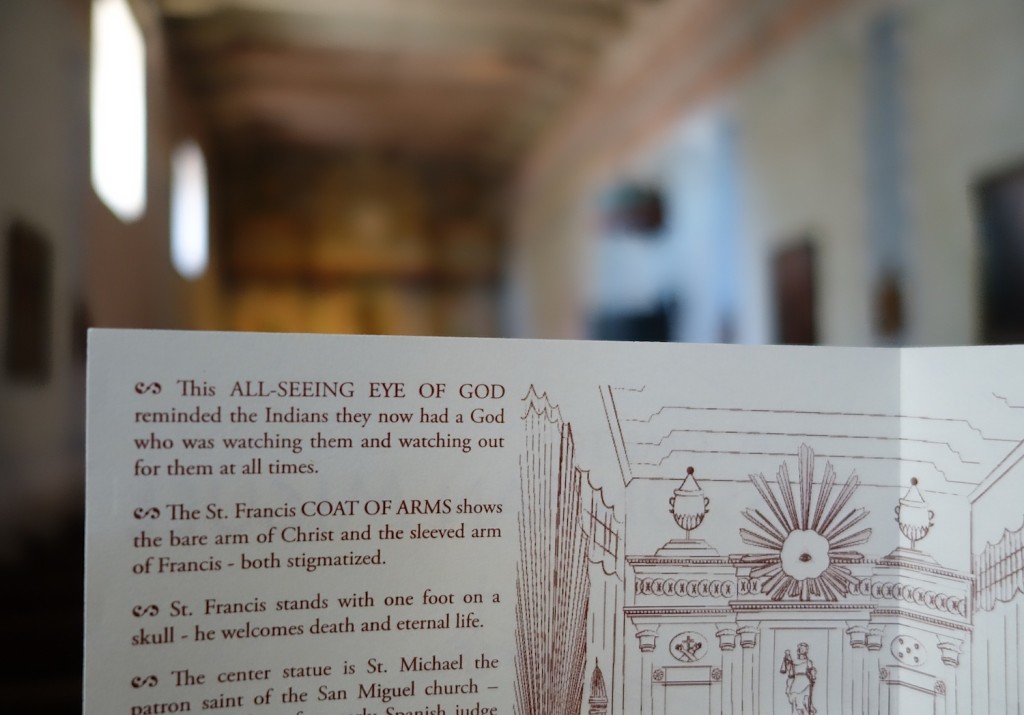

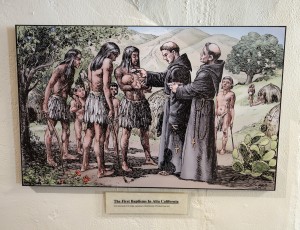

We were surprised by how many of the historic paintings loudly portrayed domination, death, and suffering. “Many Indians did not speak Spanish,” a tour guide explained. “So, these paintings were commissioned by the Padres, because a picture can speak a thousand words.” In the chapel, a prominent painting depicts a large robed man holding a cross with his foot apparently stepping on the earth. The tour brochure for the chapel describes the purpose of the large wooden eye that stands at the front of the chapel: “This all seeing eye of God reminded the Indians they now had a God who was watching them and watching out for them at all times.”

On the official guided tour of the mission, there is a recently revamped “Indian room” which contains various artifacts and depictions of how the Salinan Indians used to live. The next room moves on to describing the Spanish and Mexican periods, as if there was a clean, inevitable progression of history: no description of the conditions of enslavement, the many abuses the Native people suffered, or the terrible death toll. A brochure states that San Miguel was chosen as a location because of the exceptional number of Salinan Indians that inhabited the area. What became of those strong and independent Salinan communities?

From Mission records, we know that 2,332 baptized Indians were buried at San Miguel by 1850. We don’t have a death count for the many “heathen” Indians who refused to be baptized, because no one was keeping track. After devastating the local Salinan communities between 1798 and 1806, the Missionaries of San Miguel extended their “spiritual conquest” to the Yokuts villages to the east, especially to the large villages known as Wowol and Auyame.

To counter the myth of voluntary participation in mission life, one only needs to consult the historical records of how frequently the Indian converts attempted to escape and return to their home territories. Missionized Yokuts people, for instance, would flee to their home villages such as Wowol, only to be hunted down by Spanish soldiers:

"Wowol retained its independence but remained subject to coercion and violence. In 1816 Mission San Miguel sent an expedition of soldiers to recapture runaways, and they burnt down the village of Wowol when villagers refused to give them up." 1

Indigenous people fleeing the missions were embarking on a perilous journey with little or no supplies to aid them. Traveling great distances by foot across the rugged landscape, they were pursued by Spanish soldiers as well as Christian “Indian auxiliaries.” To further complicate matters, the safe-havens of their home villages no longer existed in many cases, especially for the Salinan people whose communities had been the hardest hit by San Miguel and San Antonio missions. Many escapees would head out eastward towards the San Joaquin Valley:

"Like runaway slaves in the American South, many struck out for distant parts, then congregated in remote areas, and formed large fugitive communities. By the end of the mission era, hundreds of runaway neophytes from Santa Barbara, San Miguel, and San Luis Obispo missions had accumulated in a swampy area of the southern San Joaquin Valley, near what later became known as Buena Vista Lake. According to Padre Mariano Payeras, they reverted to their pagan state and fought off soldiers sent to fetch them back, forming what Payeras described as “a republic of hell and a diabolical union of apostates."2

The genocidal policies of the mission system towards California’s indigenous peoples are well-documented. The Catholic Church, which continues to operate Mission San Miguel for the purpose of propagating its religion, is actively choosing to gloss over this history with images of smiling Padres holding bells. And society at large, it seems, stands in complicity. How many hundreds of children in public schools are sent to tour Mission San Miguel every year? How much taxpayer money has been funneled into ongoing efforts to restore and commemorate this site of genocide?

Page through historical records, and one finds that the missionaries even told on themselves. We propose that quotes such as the following be prominently displayed as part of the self-guided mission tour. In 1798, Father Antonio De la Concepcion Horra, one of the first padres assigned to San Miguel, authored a letter to the viceroy [ruler of New Spain] reporting on the conditions of the California missions:

"I would like to inform you of the many abuses that are commonplace…The manner in which the Indians are treated is by far more cruel than anything I have ever read about. For any reason, however insignificant it may be, they are severely and cruelly whipped, placed in shackles, or put in stocks for days on end without even a drop of water."3

Fermín Lasuén, successor to Junipero Serra as president of the California missions and founder of Mission San Miguel, issued a lengthy rebuttal to Father Horra’s stark depiction of mission life. He argued that the Indian population was of savage character and deserving of strong punishment, in order to save the Indians from themselves. He even suggested that Franciscans were punishing the Indians less than they truly deserved. Lasuén writes that California Indians are:

"…a people without education, without government, religion, or respect for authority, and they shamelessly pursue without restraint whatever their brutal appetites suggest to them. Their inclination to lewdness and theft is on a par with their love for the mountains…Such is the character of the men we are to correct, and whose crimes we must punish."4

The Spaniards regarded the Indigenous population as less than human. In 1801, Padre Lasuén writes:

"Here then we have the greatest problem of the missionary: how to transform a savage race such as these into a society that is human, Christian, civil, and industrious. This can be accomplished only by de-naturalizing them. It is easy to see what an arduous task this is, for it requires them to act against nature."5

Padre Lasuén makes clear that this project of “correcting” and “de-naturalizing” the indigenous population was dependent on military force and the continuous threat of violent punishment, to prevent the neophytes from returning to the pagan life to which they were, in his words, “still much addicted.” In 1797, Lasuén protested a proposal to withdraw soldiers from Alta California, stating that:

“The majority of our neophytes have not acquired much love for our way of life; and they see and meet their pagan relatives in the forest, fat and robust and enjoying complete liberty. They will go with them, then, when they no longer have any fear and respect for the force, such as it is, which restrains them.”6

They tell on themselves. Yet the Padre statues smile on at Mission San Miguel, as thousands of tourists stream through open doors each week, receiving their dose of pastoral, tile-roofed Franciscan fantasy.

And meanwhile, Patti Dunton of the Salinan Tribe explained to us, her tribe does not own a single acre of land in the present day. She also described how the abundance of Salinan cultural and burial sites throughout the valley floodplain are continue to be routinely bulldozed, looted, and damaged. “Even today, there’s so little respect for our people,” Patti lamented.

- Saints and Citizens: Indigenous Histories of Colonial Missions and Mexican California by Lisbeth Haas, pg. 42

- Beasts of the Field: A Narrative History of California Farmworkers, 1769-1913 by Richard Street, pg. 70

- Converting California: Indians and Franciscans in the Missions by James A. Sandos, pg. 272

- Ibid, pg. 89

- Lands of Promise and Despair: Chronicles of Early California, 1535–1846 edited by Rose Marie Beebe, Robert M Senkewicz. pg. 274

- American Colonies by Alan Taylor, pg. 463

I cried the day Serra was given sainthood. I stand with you in spirit.

Much love to you.

http://longmarchtorome.com/

I spent my novitiate year as a young friar at Mission San Miguel, 1960-61. From there we were sent to Mission San Luis Rey to complete our studies in philosophy, then on to Mission Santa Barbara to study theology. At that time we accepted the romantic view of the missions. We revered Junipero Serra, and as padre choristers, we even sang a song to him. Only in later years, after I left the Franciscans, did I come to discover the true story. I recently joined with Val Lopez (Amah Mutsun) and others to oppose the Serra canonization, and I hope that this event will unite all the tribes and bands to tell the true story and expose the colonizers’ lies that the Vatican, the California bishops, and the Franciscans are spreading. The truth needs to be told. — Mark Day

Right on, Mark. This whole fiasco makes me ill. The total disregard for the indigenous people’s of the missions and there discendants. We all know that when the first explorers came thru here, they had nothing but praise for the natives here, so the fathers straight up lied in their letters about their characters. I hope they went to their own private hell for devastating our indigenous people’s.

Pingback: Mount Diablo and Runaway Indians | Heathen Chinese