Posted on November 7, 2015

Together in the rain San Luis Rey » “El Camino Real was our Trail of Tears”

Caroline Ward Holland lighting candles and sage at the only burial marker on the SLR mission grounds for the 4,000+ Indians buried there.

On Tuesday at 5:30pm in from of Mission San Luis Rey, we stood on the steps of the chapel in pouring rain. It was dark out, except for the occasional flash of distant lightning. Nevertheless, we soon found ourselves surrounded by a circle of 20 people, standing with us in the cold. Most were tribal members of the San Luis Rey band of Luiseño Indians, though others hailed from the Pechanga band of Luiseño, the San Pasqual band of Kumeyaay, and nearby towns.

Mel Vernon, chairman of the San Luis Rey band, led an opening prayer and welcomed the walkers to Luiseño (Payómkawichum) territory. Tribal member Diana Caudell echoed his greeting. “I want to welcome people here, to our ancestral village, which is right down over there, and where the mission is now standing.”

“My great, great grandparents were slaves here at Mission San Luis Rey,” tribal member Max Moran said, with a booming voice. “We have a lot of stories about how badly they used to treat the Indians here. It’s just unbelievable, how bad. It breaks my heart in different ways. And seeing how all that is hidden, in the story they tell— everybody thinks that the missions did so much, but to us, it was just destruction. I could really go on about this— it makes me so angry.”

“I’m a former council member with the San Luis Rey band, and I’m honored to be here tonight with you guys,” said Marlene Fosselman. “Thousands of our ancestors were here at this mission. If they didn’t struggle through things and do all the stuff that they did, then we wouldn’t be here today. And even though there was a lot of bad stuff that took place, and probably still does take place, at least we’re here together. We have to teach the younger generation our own stories, the native stories— not just what books or other outside sources tell us.”

“And I just want to say that to me, I feel that the missions are a small part of our history,” Marlene added. “But we’re a huge, gigantic part of theirs. Because if they didn’t have all of us, then they wouldn’t have this. (gesturing at the mission)”

“It’s good to be here, and to see respect being paid to the Luiseño people,” said Jim Igo of the San Pasqual band of Kumeyaay. “I always call El Camino Real our Trail of Tears. Our people had to walk before the crack of the whip. It was more like herding cattle, they say.”

In his exhaustively researched book entitled Beasts of the Field: A Narrative History of California Farmworkers, author Richard Street offers a similar accounting of the conditions the Indian field hands at the missions were forced to live under:

"At San Luis Rey mission, alcaldes supervised every phase of life, from fields to church. Visiting the mission in 1829, the Massachusetts hide trader Alfred Robinson observed field hands daily attending mass and being ‘driven along by alcaldes, and under the whip’s lash forced to the very doors of the sanctuary.’"

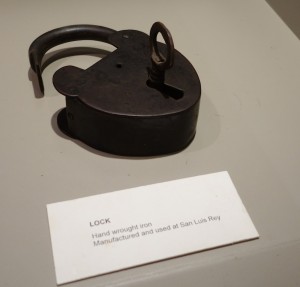

“It’s definitely a really happy story that they’re telling at the missions,” said walk supporter Cat Wilder. “There’s nothing in this mission, or in any mission that we’ve been to, about the forced labor conditions, or the abuse, the shackles, whippings, or the prevalence of rape in the mission system. There’s nothing about that.”

“They really like to say how the goal of the missions was to create a self sufficient, independent community,” Cat added. “And that’s so ironic because actually, they came over here and utterly destroyed the self-sufficient, independent communities that lived here for thousands of years.”

We were pleasantly surprised by the attendance of Mark Day, a journalist who studied for years with the Franciscan Order. “I’m a former Franciscan, I studied here at this mission for four years, also at Santa Barbara and San Miguel. We were fed all the myths and legends, as you probably know about. And we gave tours of the mission. It wasn’t until years later that I began to realize exactly what it was— that we were telling lies. So lately, I’ve been actively opposing the canonization of Serra. I’m Irish-American, so our people know what imperialism is all about. I’m very happy to be here with you.”

“I’m Luiseño too, from the Pechanga band in Temecula,” a man named P.J. said. He shared that in 1998, he participated in the Walk for Sovereignty and Unification, otherwise known as “S.O.S.,” the Solidify Our Sovereignty walk, which also followed El Camino Real, bringing together California tribal nations. “With Robert John Knapp, we actually went the opposite direction, we went north, starting from Pala. So, I know its a struggle. But we carried on, Robert John was a trooper, and at the end we held a bear dance in front of the capitol in Sacramento.”

“You know how in the stories they have at the different missions, they act like, oh well the Indians, and they’re talking like we’re in the past,” P.J. said. “But as we all know, we’re still here. And we’re not going nowhere.”

“Abuse is not easy to talking about, the abuse that’s going on, or that has happened in the past,” flute maker and San Marcos resident Jon Sherman said. “So it’s good to hear people talking about that. Because it’s always hush hush, you don’t talk about those things. And so, it continues. If its not talked about, if its not recognized, then it doesn’t change. So, I deeply appreciate hearing these stories today.”

The rain began falling down more profusely, and chairman Mel Vernon announced that it was time for us to move indoors to the nearby Pablo Tac Hall, an old building named after a famed Luiseño scholar from San Luis Rey. There, San Luis Rey tribal members brought in a drum and five men sang a powerful series of songs. Little bits of stucco were falling from the ceiling as the room reverberated with the pounding of the drum.

Next, we migrated over to the warm refuge of the San Luis Rey Bakery, which the Mendoza family had kindly kept open for us past their usual operating hours. Over dinner, more stories were shared, and a microphone was set up for a couple of Walk representatives to share some words. Caroline Ward Holland summarized some of her reasons for initiating the Walk.

“The signs at the missions all say that they helped the native people, and they did this, and they did that,” she explained. “But the truth is, most of our people remained at the missions unwillingly. They did not want to give up their culture, they did not want to lose their children, they did not want to be here. Eventually, they learned how to live within that system, but that’s where we lost everything.”

“Of course, I don’t want to live in the past, and I want to go forward and forgive. But there has to be some kind of admittance of injury, and they’ve yet to do that. They haven’t even recognized us as people. Their Doctrine of Discovery says that they were the first human beings here. It still says that. It’s 2015, and it still says that.”

Someone asked how it is that Serra could be granted sainthood, anyways— “don’t saints have to perform miracles?” It was explained that the first miracle was pretty much a sham— a nun in St Louis claimed to have been cured of a terminal illness after praying to Serra (see Serra’s Miracle Nun). And the second miracle? That requirement was arbitrarily waved by Pope Francis. “Well, actually, the second miracle is that we’re still here,” Caroline remarked, laughing.

“When we started this trip, I was angry. At the Catholic Church, and about the whole Serra issue,” walk co-leader Kagen Holland said. “But after walking close to 700 miles, I don’t have the energy to be angry. It just detracts from the respect and love that I have to show for my people and all our cousins, all the way down the coast.”

“I hope that through this, our people can find some healing,” Kagen concluded. “You know, there’s so much trauma in our communities. I hope that our people will be able to stand together on more things. And I’m great to meet all the tribal elders and people along the way, and I just have such a better understanding of California, the land, and people, and history. So, I just want to thank you all.”

Thank you for caring enough to move your initial anger into something profound for all of us. Many have been watching and are with you. I feel humbled by your direct action.